The idea of coming to visit Antarctica appealed to me. More to add to my ever-growing list of places that I had been to, than anything else. By now you must have guessed that Jill and I are about going to as many new places as we can and exploring some of the less visited places that our planet has to offer. And Antarctica was too good to pass up.

And it really was good.

As part of the Ultimate World Cruise that was being run there was a leg that went down the east coast of South America, around Cape Horn (the bottom bit of South America) and up the Western coast. Along the way the ship would be visiting the Falkland Islands, stopping in the southernmost city on the planet (Ushuaia, Argentina) and then going into Antarctica. Specifically it would be going to:

- Drake Passage

- Gerlache Straight

- Dalhan Bay

- Paradise Bay

- Elephant Island

This itinerary took in a fair chunk of going past the South Shetland Islands and took us into the Antarctic peninsular proper. You need to note that only little boats can port at any of these, so we were there without landing.

Lets be honest right up front, my knowledge about Antarctica before coming here was almost nothing. It was big, cold and full of seals, whales and penguins. That was about it.

I have never been a sailor, know very little about navigation and only had a cursory understanding of latitudes and longitudes and knew nothing about winds. But until I started getting close to and experiencing some of the seas as we rounded Cape Horn I was oblivious as to how little I actually knew.

To say that this is a foreign environment to me is possibly the biggest understatement yet. So this post will be about following me on my journey of discovery about just how ignorant I was about anything nautical, navigational, or Antarctic-related. So lets start with some basics.

How big is Antarctica?

Antarctica is the fifth-largest continent and is about 5.5 million square miles (14.2 million square km) in size. It is the world’s highest continent, with an average elevation of about 7,200 feet (2,200 meters). This is the same height as Australia’s highest peak (Mt Kosciuszko).

It is also the driest, windiest, coldest, and iciest continent. If all of the ice in Antarctica melted, sea levels would rise by around 60 metres.

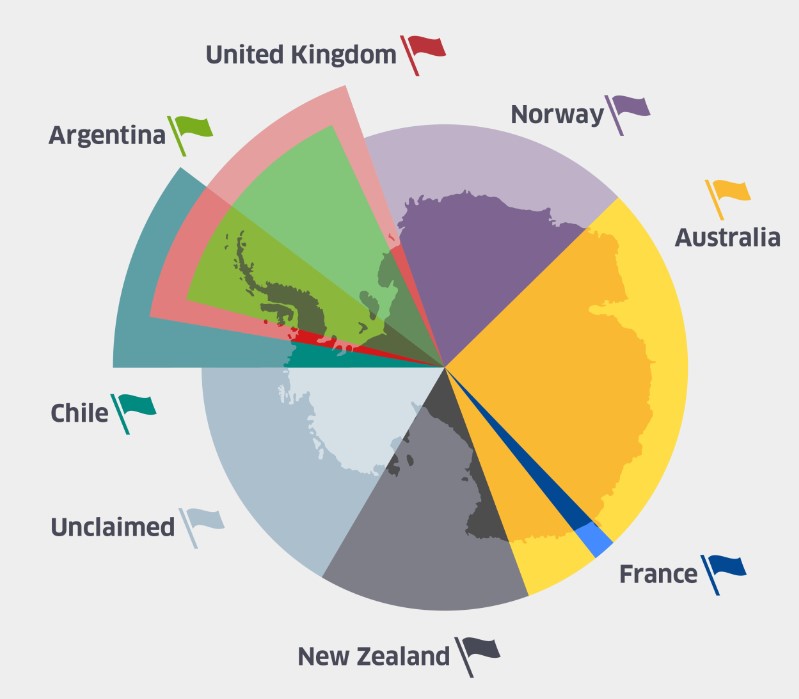

Who owns Antarctica?

There is no single country that owns Antarctica however there are seven nations (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the United Kingdom) that claim rights over some of the territories.

In 1959 the Antarctic Treaty was signed by the twelve countries that were active in Antarctica during the preceding years. This included the seven with territorial claims and also Belgium, Japan, South Africa, the United States and Russia (USSR). The treaty designates Antarctica as a continent devoted to peace and science.

The main aim of the treaty was to ensure that no nation militarised the region (during the cold war). Most importantly to establish it as a zone free of nuclear tests and the disposal of radioactive waste.

Article 1 of the treaty was that it is used for peaceful purposes only; Article 2 was that they promote international scientific cooperation and Article 3 agreed to the sharing of all scientific observations made.

Since 1959 a further 44 countries have acceded to the Treaty.

Many other nations are joined in multinational projects conducting research in the Antarctic.

How cold does it get?

Almost 98% of the continent is covered by ice that is around 1 mile thick. Antarctica has the lowest ever recorded temperature on the planet. In 1983 the Vostok Research Station recorded a temperature of −89.2 °C (−128.6 °F ).

Can things live there?

There are about 800 species of plant and plantlike organisms (mostly moss and lichens) in Antarctica. The cold climate (officially categorised as a desert) and lengthy winter periods of total or near-total darkness support only limited plant and plantlike organisms. The Antarctic holds about 90% of Earth’s fresh water but it is locked up in 30 million cubic kilometres of ice.

Do people live there?

There are no actual cities or villages as 98% of the continent is covered by ice but there is a permanent population of around 1000. These people are employed at one or other of the (70 odd) research stations (operated by 25 countries). This can swell to around 4400 in the summer and there is usually another 1000 doing research on vessels in the region.

Wildlife

It is the only continent on Earth with no terrestrial (land) mammals but is home to a range of marine wildlife and birds, mostly made up of penguins, seals and whales. There are no polar bears in Antarctica.

Of the 18 different species of penguins on the planet, 8 of them inhabit Antarctica. These are the Emperor and Adélie that can only be found on the Antarctic continent, while Chinstraps, Macaronis, Gentoos, Rockhoppers, Magallanics, and Kings can also be found in sub-Antarctic locations. Info and photos from www.penguinsinternational.org.

There are 8 species of whales that are commonly seen in Antarctic waters. Southern Right, Sei, Humpback, Fin, Antarctic Minke, Sperm, and the enormous Blue whale spend part of every year near Antarctica, as do Orcas (Killer whales).

The Antarctic waters are also home to 6 different species of seal. Ross, Weddell, crabeater, leopard, fur, and elephant seals are all found here.

The South Pole(s)

There are two South Poles. The Geographic South Pole – where the Earth’s surface intersects the Earth’s axis of rotation and the Magnetic South Pole – where the direction of the Earth’s magnetic field is vertically upwards. The Magnetic South Pole lies almost 3,000km from the Geographic South Pole and moves at the rate of about 5km/year.

Daylight – Almost all of Antarctica lies south of the Antarctic Circle. This means that during the summer, the Sun never sets below the horizon, no matter where you are on the continent. Our days had about 3 hrs of darkness(ish) between midnight and 3am.

Antarctic Winds

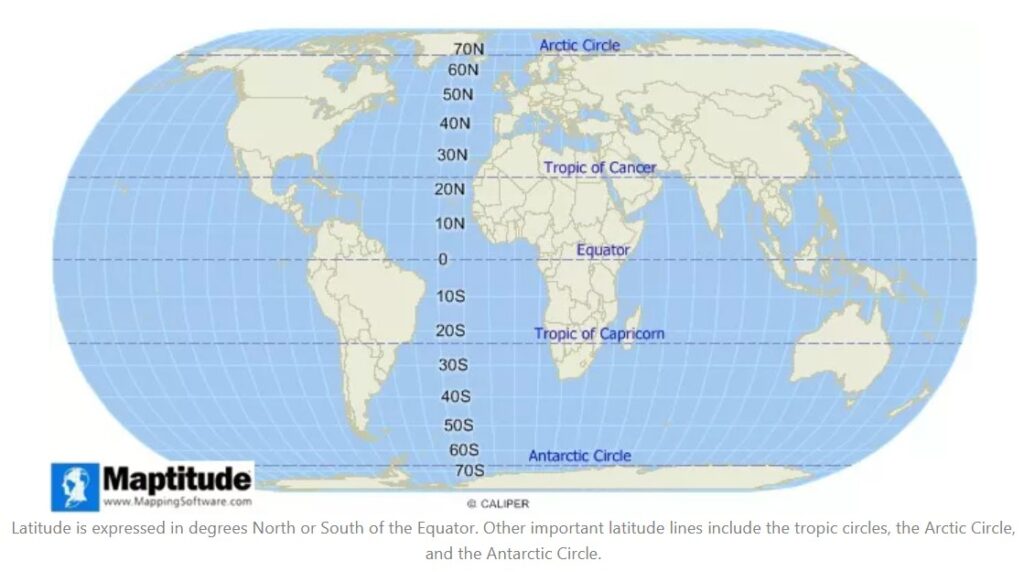

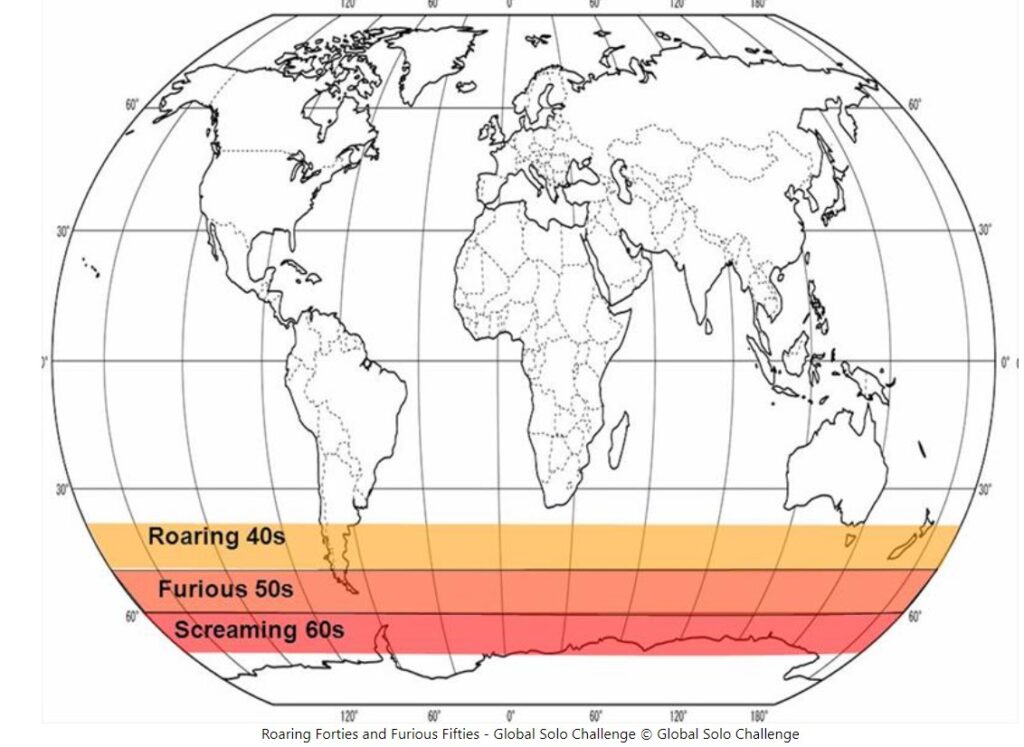

Up in the rest of the world, there are mountains, buildings, cities and general stuff that wind hits, slows down or diverts around (generally west to east). At about 40° latitude (from the equator) this stuff largely goes away. Sure Tasmania, New Zealand and a bit of South America are in the way, but for the most part, the winds just hoot around the world unimpeded. Between the latitudes of 40° and 50° south these winds are known as the roaring 40’s.

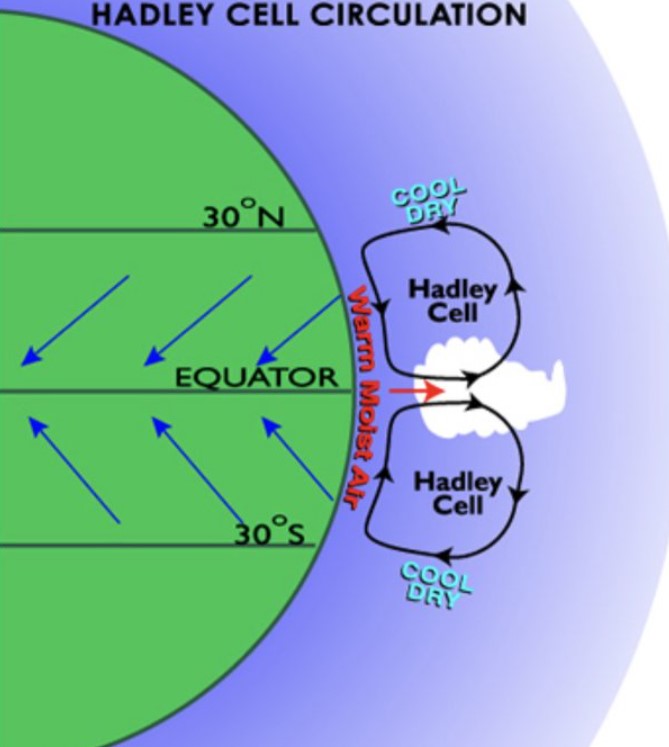

To explain this movement of air I will steal and paraphrase from experts because I will likely bugger it up. Hot air at the Equator rises while the air at the poles is cooler and therefore sinks. Equatorial air is pushed towards the poles by cooler air travelling towards the Equator. This happens beautifully until about the 30° mark. If Earth wasn’t rotating, this differential heating would cause warm air to rise near the equator and flow towards the poles in the upper atmosphere, while cooler air flowed from the poles to the equator near the surface.

At about 30°S, the outward-travelling air sinks to lower altitudes, and continues toward the poles closer to the ground (the Ferrel Cell).

At about 60°S the air joins the Polar vortex and rises up again creating a wind circulation thingy (the last bit was me again).

This travel in the 30°–60°S zone combines with the rotation of the earth to move the air currents from west to east, creating westerly winds. So, the Roaring Forties howl around the world with minimal interruption between 40-50 degrees. This was great back in the day that you had a sail boat and wanted to sail east, not so much if you wanted to go the other way.

By the time you get to 50° New Zealand and Tassie bugger off and all there is to hit is the tip of South America. So 50°-60° has become known as the Furious Fifties and 60°-70° the Shrieking or Screaming Sixties.

I found an old sailors saying that claimed that “below 40° South there is no law and below 50° there is no god“.

But what does all that mean?

It means that the wind in the roaring 40’s hurtles along at 15 to 35 knots (27-65 kph) with gusts averaging around 70 knots (130kph). And the further south you go the faster the winds get. I could not find a quantification of how much faster for the 50’s and 60’s but I did manage to find that the gusts reached over 100 knots (200kph) during the spring and autumn months.

The difference in temperature between the Antarctic ice and water creates turbulence, which in turn results in intense depressions. These all combine to produce open ocean waves of up to 10 meters (33 feet). Add to this the phenomenon of “rogue waves”. These are unusually large, unpredictable, and suddenly appearing and have been measured at over 30 meters (100+ feet). Old mariners’ tales had claims of up to 200 feet but this is unlikely.

So what about Us

Education over… holy crap this place is amazing. Our first introduction to this (and the reason for the lengthy educational setup) was when we popped out the bottom of South America (around the 55° mark) to where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet. At this point we were smashed in the face by the wind.

This phenomenon is known as a williwaw wind which is described as ‘a sudden violent gust of cold land air common along mountainous coasts of high latitudes’. What it meant was that we were hit with these gusts that come suddenly, frequently, and unpredictably.

With bigger winds come bigger waves. So we bounced and bobbed around as we crossed the Drake Passage (the gap between South America and the Antarctic peninsula).

Having reached the relative calm of the Antarctic peninsula and the South Shetland Islands we found ourselves in the realm of icebergs aplenty. Add to this some pretty spectacular icy cliffs and mountainous shorelines and we were having a damn good time.

The first really big iceberg that we came across was a stunning one with arches that had formed as the ice broke away from the main block. We also learned that Jill and I both suck at selfies.

This continued for the next 3-4 days. In this time we stopped at the various places outlined in the itinerary (earlier) and spent most of our time hunting for wildlife. The combination of stunning scenery and the frequent burst of a whales blowhole that prompted the search for the rest of the whale created some pretty good times.

The second morning we woke to a deck that was covered in snow and a very excited crew who typically hang out in Asia and the Caribbean and for the most part had never seen snow before. This made for some amazing scenes as they ran about trying to eat snowflakes as they fell, built snowmen and generally just frolicked about.

As the cloud burnt off we resumed our wildlife hunt. The first obvious ones to be seen were when we sailed past flat icebergs. You could see little specks on the icebergs. Thankfully Jill has a 50x zoom on her camera, which revealed that these little dots were something a little more interesting.

And while on the same topic, as the boat belted along you got to see these specks shooting off either way to avoid being run over.

This became a common occurrence as the day progressed.

After our penguin escapades were the whale sightings. And there were many. Most of the sightings were limited to the blowhole bursts and the dorsal fin and back arch as they cruised on past. But every now and then you would get the full show with the tail popping out of the water. We even got a couple of breaches where they come right out of the water, but getting these on film is a whole other matter.

Oh, while Jill’s selfie skills might be lacking, she does capture some pretty damn fine videos though.

And some more…

On day one we saw southern Right Whales and Humpbacks. On day two, around sunset, we had about 25-40 minutes of Blue whales rocking past. Not an orca in sight sadly. Oh and did I mention the random stunning icebergs…Yeah, I probably touched on it.

At one point when we stopped in Paradise Bay the captain sent down a small boat with a professional photographer to get some PR shots for the ship. While doing that they also lassoed a small iceberg and wrangled it up on deck for us all to play with.

Something that we didn’t see but that fascinated me when researching was the Bloodfalls.

Blood Falls is a waterfall where the water is high in salt and oxidised iron. When the water comes into contact with air, the iron rusts giving it an amazing red colour.

To say that this is a once-in-a-lifetime experience is probably pretty redundant. But wow, if you are looking to build a bucket list, then this needs to be pencilled in there somewhere.